After talking to CEOs, LPs and consultants during several recent annual meetings, it has become clear that liquidity is the hot topic. CEOs who have been running companies over 5+ years said more than half of their investors are pushing them to be IPO ready or think seriously about the eventual sale of the business. About half of those we spoke with are preparing to go public at some point and half are expecting an eventual sale of the business. When asked, most have an idea of what price they would accept from a potential buyer today. Of course selling in the future would yield a higher price (assuming the company continues to grow), but the uncertainty of the market is always important to take into consideration. Regardless, many CEOs are thinking the right way, which is to always know where they stand in the risk/return spectrum as it relates to exit price and timing. Note: We appreciate how much time and energy it takes to build a world-class, $100M revenue company. This piece is to outline our thoughts on venture capital portfolio construction, from an LP’s perspective – it is not a discussion of the success of a company or its exit.

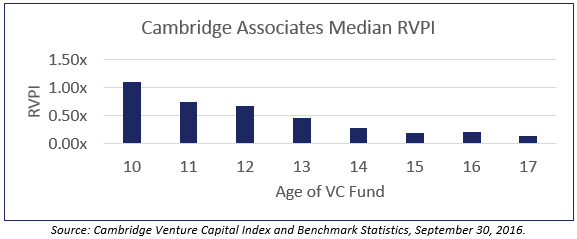

In that same vein, LPs are comparing notes and talking about the relatively low DPI numbers. According to Cambridge benchmark data as of 9/30/16, after 10 years the pooled mean RVPI for 2007 vintage year funds is still 1.1x! That means there is still a little more than the total amount an LP committed still sitting in unrealized value. A fair point to make is that for the same age fund those same VCs have given 1.0x back to their LPs. Said another way, only half of the total value of the funds is in the hands of the LPs after the 10-year life of the fund. After 12 years, the pooled mean RVPI for a venture fund is still 0.7x. That means 70% of the total amount LPs gave the VC to invest is still unrealized.

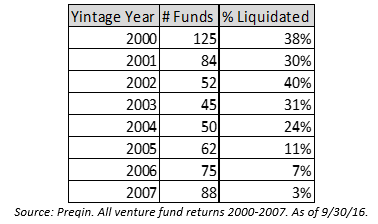

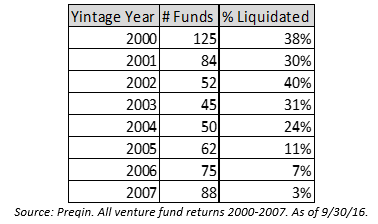

The typical life of a venture fund is 10 years plus up to 2 one-year extensions, so in a perfect world there shouldn’t be any value left after 12 years. Historically, LPs invested in private equity funds with the understanding that Fund 1 distributions should cover Fund 3 capital calls, or in other words, a commitment to several funds in a row should be cash flow positive with the third commitment. But this hasn’t been the case as time to liquidity has lengthened. Looking at Preqin data for 2000-2007 vintage year funds as of 9/30/16, only a small percentage of funds have actually fully liquidated.

Every LP comes at their portfolio construction strategy in different ways and with different objectives. All want strong relative performance to the public markets, but some LPs are more focused on generating a certain multiple of capital invested while others are more focused on an IRR hurdle. Ideally – we want both. Furthermore, some LPs have a strong need for distributions in order to satisfy cash flow requirements. Others enjoy the luxury of managing long term capital and can afford to wait for liquidity. Strategic LPs not seeking performance first are few and far between.

LPs with closed end funds (i.e. Fund of Funds) need to wrap up their own funds in approximately 15 years. These investors have to worry about the timing of cash flows and interim performance numbers since they have to raise capital as well. Public pension funds typically benchmark to an IRR-like number that equals public market performance plus a risk premium, and most have to carefully manage cash flows with regards to their funding ratios. While endowments and foundations can have longer time horizons, they often have operating budget and grant obligations to satisfy and therefore require a steady liquidity stream as well. Most LPs have a board or other managing body that determines allocations to the venture space. Expected performance and risk are important factors in that decision. Some are J-curve adverse because they can’t afford to take the interim performance hit. One reason may be for asset allocation weightings – a decline in the value of the venture portfolio could inadvertently skew their asset allocation thresholds. Another reason is that employee bonuses could be tied to annual performance.

As we begin investing our new fund later this year, we are spending more time and resources looking at the ideal portfolio construction to optimize both multiple and IRR. We know other LPs are doing the same. In addition, we are actively encouraging our VCs to liquidate public stocks as soon as practical because small increases in the stock price over a longer time period generally is not helpful to LPs focused on IRRs – even though it may be profitable to the VCs and their carry.

To keep the venture model working well, we’ve always said that there needs to be a healthy balance of innovation, capital and liquidity. Innovation is as good as it has ever been. Capital inflows are high, but more reasonable now that we are seeing less from the “tourist investors.” Currently, liquidity is lagging, but the opportunities are there, especially among publicly-held stocks and other mature, “exit-able” companies.