Introduction

You don’t have to be a brain surgeon to know that investing in healthcare startups has been tough lately. Returns in healthcare investing have not been stellar for the past several years, particularly compared to returns for high-tech companies, some of which (Facebook, Splunk, LinkedIn) are finally going public and generating sizeable profits for their early venture capital backers. This has caused many healthcare investors to shy away from making new, early stage investments—just as they did during the first dot- com boom in the late 1990s, when most VCs rushed to back hot technology companies over drug and device startups.

In healthcare today, the medical device sector is the most wounded, thanks largely to a disorganized and extremely slow-moving U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which approves new devices. Biotechnology investing—traditionally the riskiest, but potentially most profitable area of healthcare—is also suffering as many cash-strapped investors have lost patience for lengthy, expensive clinical drug trials. Some skittish investors have abandoned biotech investing altogether; our managers tell us that today, fewer than 20 venture capital firms are actively investing in healthcare startups.

But we believe healthcare investing can still offer steady M&A returns, and there are other healthcare sectors in better shape right now that deserve new investment. These include healthcare IT and technology-enabled healthcare services, such as using new technologies like cloud computing to drive efficiencies and improve services provided by doctors and hospitals. There are also positive signs in the specialty pharmaceuticals market where companies are experimenting with emerging new business models that can lead to quicker returns for investors. Most importantly, large, potential pharmaceutical acquirers, such as Abbott, Allergan, Amgen, GSK, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi, continue to reduce their R&D spend, meaning they need to buy innovative companies and have plenty of cash on their balance sheets to do so.

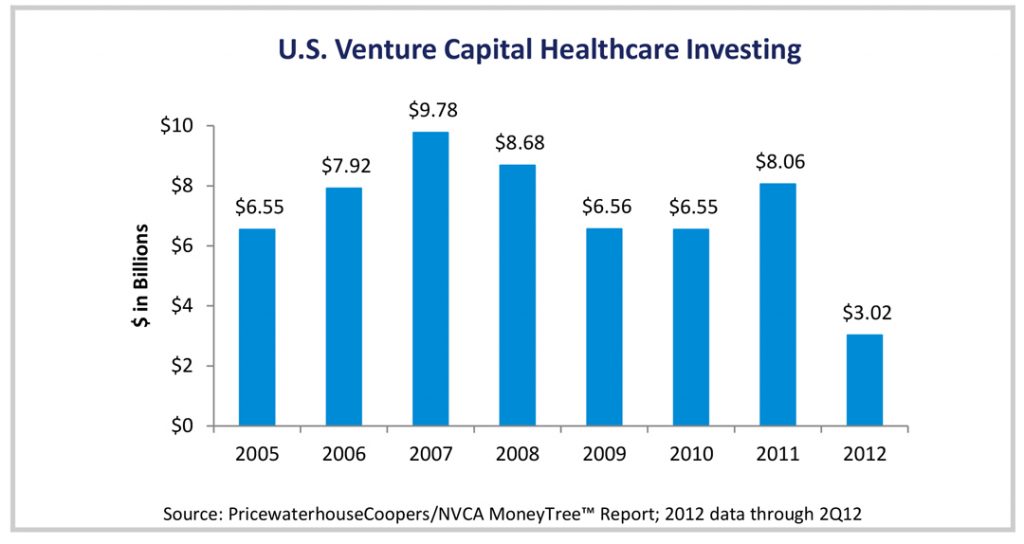

Still, while the widely tracked NYSE Arca Biotechnology Index is actually up about 30% through June 30th of this year, compared to just 10% for the NASDAQ, the public markets have not been as receptive to new healthcare deals as technology offerings lately, and that has negatively impacted venture capital investment in healthcare. Last year, according to ThomsonONE.com, only a quarter of the 53 venture- backed IPOs in the U.S. were healthcare companies. Through the first half of 2012, only 23% of the 30 venture-backed IPOs were healthcare companies. While there are certainly reasons to take pause as a healthcare investor right now, we believe there are pockets of potential returns. This paper highlights how we view the healthcare investing landscape right now.

The Root of the Problem: Regulation

Healthcare investing is being challenged by a number of factors. But a slow-moving FDA with high turnover and lack of transparency is one of the chief culprits, particularly when it comes to medical devices. Last year, a survey by the National Venture Capital Association—which queried 156 firms managing more than $10 billion in healthcare investments—found that 39% had decreased their healthcare investments over the past three years. Notably, 61% percent of the firms named “regulatory challenges” as the key driver behind their decision.

Despite an uptick in drug approvals last year, some venture capitalists complain that the FDA generally has trouble getting its arms around innovative technologies; with new drugs and devices, the agency wants “everything to be known upfront,” said one VC. But that is often impossible, as medical devices, for instance, are traditionally modified and perfected after they have gone through some level of human trials. Dysfunction in the FDA’s device group appears to be greater than on the pharmaceutical side, where regulators generally have to approve or reject new drugs within 12 months. There is no such deadline for devices. In addition, medical devices usually serve smaller markets than new drugs, so revenues for device companies are smaller, making regulatory delays even more harmful. FDA approval rates for some devices are now running roughly four years behind comparable rates in Europe for a CE Mark, a designation for meeting European health, safety, and environmental standards. This has pushed many healthcare companies to launch new medical devices overseas first, even though most device companies must eventually serve the U.S. market to generate significant revenue and profits.

While the pharmaceutical market is somewhat healthier, the FDA is still hindering many drug companies’ prospects. Numerous drug trials are being conducted overseas where regulations are less onerous. Regulatory delays in the U.S., of course, boost startup costs and force VCs to invest more capital into these companies to keep them afloat. And with overall industry returns still lagging, many VCs don’t have the reserves to continue to support and invest in these companies as they are subject to these regulatory uncertainties.

Many VCs cite recent, high-profile drug recalls, such as Avandia and Vioxx, as one reason the FDA is so focused on safety with respect to new drugs. Others say the FDA also seems poorly managed and disorganized. Jean-Francois Formela, a partner at Atlas Ventures, was quoted in the Boston Business Journal last year saying that one of his biotech portfolio companies recently beat the odds and gained FDA approval for a new drug. But later, the FDA disapproved of how the company labeled the drug— specifically, the size of the lettering on the packaging. It rejected the company’s application for that reason. Formela fears the snafu will delay the launch of the drug by months. “It’s like a Special Forces obstacle course—the company jumps over all the hurdles, and then they get to the end of the race and are told they have to go back and do it again,” he told the Business Journal.

Signs of Life

But we don’t think the news is all bad. After some over-funding in certain medical device sectors, such as treatments for spine ailments and obesity, the device market has shaken out somewhat, and the best- quality companies in these sectors and others are rising to the top—and surviving the FDA’s mercurial approval process. In late 2010 for example, Medtronic paid $800 million to acquire Ardian, a company that makes a catheter system to reduce hypertension. Around that same time, Sadra Medical, which makes a device to replace aortic valves, was acquired by Boston Scientific for $193 million, with a possible additional $193 million in payments if the company meets certain milestones. Lastly, two-and-a- half years ago, Johnson & Johnson spent a hefty $785 million to acquire Acclarent, which makes a balloon-catheter system to treat blocked sinuses.

Broadly, we find that healthcare companies selling products for which an insurance-reimbursement code already exists can simplify product launches and cost less to promote after approval. In essence, these companies have an attractive business model since the reimbursement hurdle is not an additional cost or time hurdle. Similarly, drugs and devices used in treatments for which patients are willing to pay out-of- pocket may also gain revenue traction more quickly. Ophthalmology treatments fall into this category; another example is dermatology. Venture firms have funded Dermira, a promising start-up that is developing topical treatments for severe acne. Many parents are willing to pay out of their own pockets for acne treatments for their teenagers. One of the most commonly prescribed, current treatments for severe acne, Accutane, is a drug with multiple side effects that requires intense regulatory oversight. The FDA also has been more willing to grant fast approval for drugs to treat rare, “orphan” diseases—another ray of hope in the market.

These trends and others have led to some significant, recent healthcare exits, mostly in the pharmaceutical space. Investors realized ample profits last year on the $750 million sale to Ireland’s Shire Pharmaceuticals of Advanced BioHealing, an innovative company that makes a bio-engineered, human- skin substitute. Canaan Partners saw a 15x return on that deal. Advanced BioHealing had been profitable for many years before its sale and was able to take advantage of existing insurance reimbursement codes when its product came to market. Another win for healthcare VCs was last year’s sale of pulmonary- fibrosis drug company Amira Pharmaceuticals to Bristol-Myers Squibb for $325 million upfront and additional milestone payments of $150 million. Also last year, Japan’s Daiichi Sankyo bought melanoma- drug maker Plexxikon for $805 million and possible milestone payments of $130 million. Just last month, Jazz Pharmaceuticals closed its acquisition of specialty-pharmaceutical outfit EUSA Pharma for $650 million. Two years ago, there was another big specialty-pharma exit when Gedeon Richter scooped up Switzerland’s PregLem for over $150 million upfront and around $455 million in milestone payments. PregLem focuses on gynecological conditions and infertility.

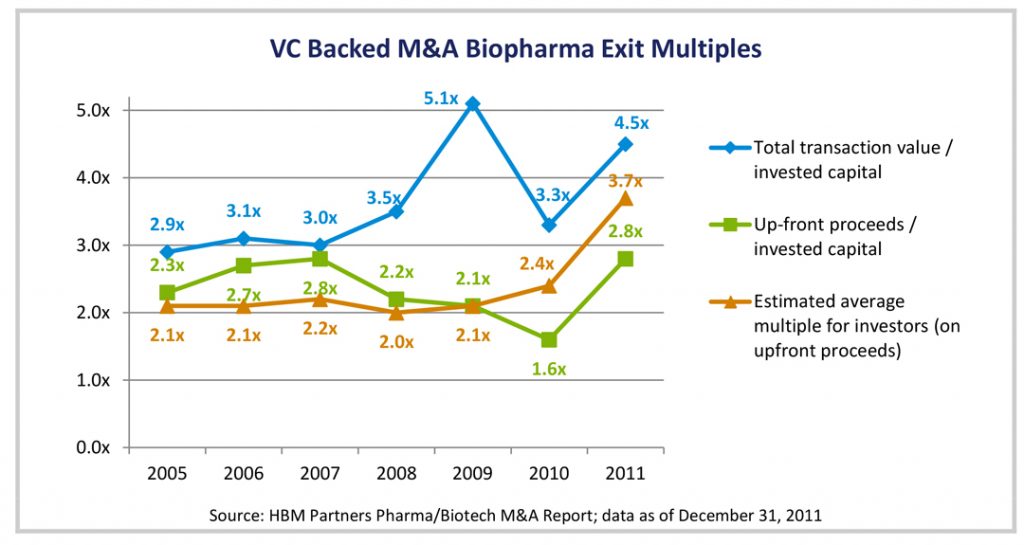

In the first several months of 2012, there were at least nine exits for venture-backed, therapeutic biotechnology companies, according to a recent op-ed piece in Forbes by Bruce Booth, a partner at Atlas Ventures. These included Celgene’s $925 million purchase of cancer-therapy company Avila Therapeutics and Dainippon Sumitomo’s agreement to buy Boston Biomedical in a deal potentially worth $2.6 billion. In most transactions highlighted thus far, the upfront purchase price was much lower than the total, potential payout if the acquired companies hit predetermined clinical and/or commercial milestones as shown in the chart below. In the Boston Biomedical deal, for example, Dainippon paid only $200 million up front, but committed to further payouts if certain milestones were met.

New Healthcare Business Models

One new business model biotech companies are using to improve their chances of a successful exit is to partner with larger pharmaceutical companies earlier in the clinical trial process, essentially offloading some of that expense to a partner instead of shouldering it themselves. Others are trimming staff costs by hiring contractors instead of full-time employees. A company might need a toxicologist to run tests on a new drug, for instance, but can save money by hiring one as a contractor for a year, instead of bringing on a full-time employee. Many drug development companies outsource work even further, to countries like China and India, to save money. Many of these start-ups are “virtual companies” because outside, clinical research organizations are doing the bulk of their work.

In another model, some investors are backing spin-outs from larger pharmaceutical companies that have already devoted a significant amount of time and resources to developing new drugs. One example is Durata Therapeutics, a spin-out from Pfizer that focuses on new types of antibiotics. The company was formed in 2009 and backed by a VC syndicate. Durata successfully completed an IPO in July 2012, just 3 years later. Finally, the market for PIPEs (private investment in public equity) in healthcare remains robust. One variation of this model is when investors essentially take over a small, already-public shell and use that company as a vehicle for a new enterprise with new products and new management. Cancer drug company, Algeta, based in Norway, is one example of this healthcare investment model.

In addition, we see opportunities in less-regulated areas of healthcare, such as healthcare IT and healthcare services. Though some “wellness” companies can be difficult to monetize, there is huge potential for companies that can marry software or other technological innovations with healthcare, such as by creating new types of electronic medical records or products that can measure individual fitness and activity levels. One such product is the Fitbit, a sleek device from a venture-backed company that tracks steps, stairs, and calories burned. More broadly, with healthcare costs still soaring, hospitals, doctors, and insurance companies continue to look for other ways to run their organizations more efficiently, and innovative start-ups are rising up to provide solutions. For example, we are co-investors in a software company called Awarepoint that helps hospitals track medical equipment and monitor staff compliance with rules such as infection-containment protocols. Government healthcare reform is expected to drive innovation in this area.

Conclusion

Our approach to the still-evolving healthcare market is to focus our resources on the small subset of managers we believe have the right strategy, teams, and capital base to navigate this volatile environment. In many cases we have found that the healthcare teams of established, multi-sector funds have outperformed many of the healthcare-only managers, and in a couple of cases has led to the spin-out of these groups from their multi-sector firms. In addition, we are very excited about our more recent relationships with healthcare-only firms such as Abingworth, Sofinnova Ventures, and SV Life Sciences, and are considering newer/emerging managers and spin-outs that we believe have demonstrated the ability to produce outsized returns from healthcare investing over the past several years. We seek to invest today with firms that have faster write-ups and exits than the more traditional healthcare-focused managers. Overall, we have been reducing our healthcare exposure since 2005 and concentrating our investments with the most-promising managers. We are now targeting an overall healthcare exposure of 15-20% versus a historical target of 25%.

That said, we still like the diversification that investing in healthcare provides within our venture capital funds of funds’ portfolios. We believe innovation in healthcare is definitely continuing, as talented scientists develop new treatments and drugs for a variety of medical conditions. Furthermore, with the reduction in capital and number of funds investing in healthcare, the competition for deals and investment valuations is significantly lower, possibly leading to higher returns in the future. Our job is to pick the right set of managers to take advantage of these trends.