Introduction

The headlines today are full of stories about small investors—variously called angels, super angels, or micro-cap VCs—participating in sought-after deals, particularly in the consumer internet space. These small, seed stage investors have backed heavyweights ranging from Facebook to Zynga to Dropbox, often at more attractive prices than traditional VCs paid when they invested in these companies later.

But behind the scenes, traditional VCs have gotten in on the action as well. Seed stage investing by larger venture firms has quietly blossomed over the last several years, enabling seasoned, early stage investors to get access to hot deals along with their angel competitors. While venture capitalists historically have done seed stage investing, many brand-name VC firms are still ironing out the logistical kinks of how to make much smaller investments— usually in the sub-$500,000 range—work in the context of their existing fund structures. It is clear, however, that seed stage investing is on the rise and may ultimately benefit investors in many mainstream VC funds.

Planting Seeds

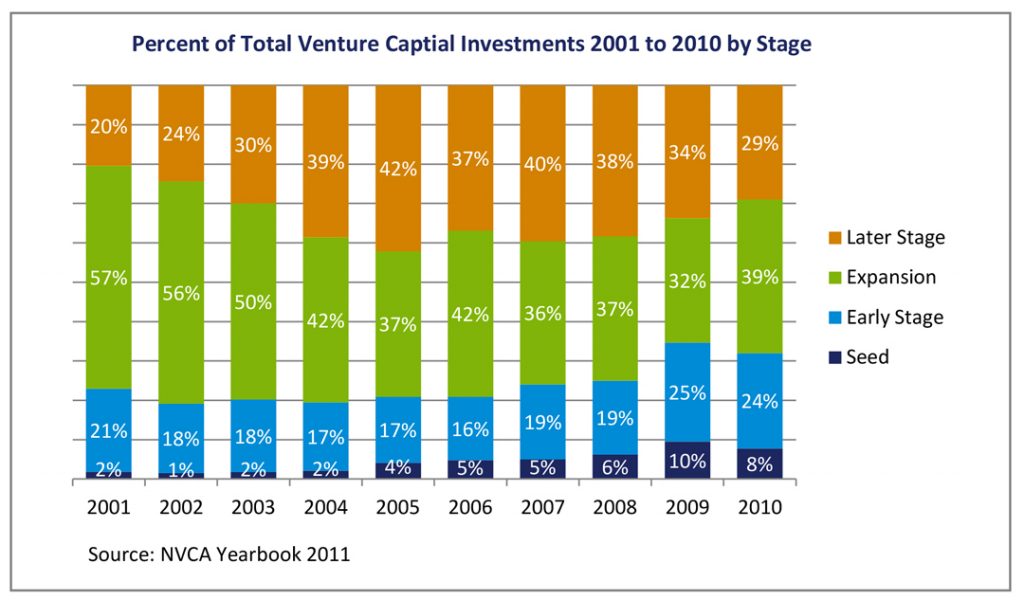

According to the National Venture Capital Association, 8% of VC dollars in 2010 were invested in seed stage opportunities, as opposed to early, later, or expansion stage. That figure was down slightly from 10% in 2009, but it represents a marked increase from several years ago. In 2006, only 5% of dollars invested were classified as seed; three years earlier, the figure was a paltry 2%.

Venture capital firms such as Accel Partners, Charles River Ventures, and others began doing seed deals in a new way several years ago. Now, many VC firms have formalized their seed stage investing programs, dedicating specific team members to scout out smaller deals. Others simply carve out a small percentage of their existing funds and impose less stringent investment rules on investments of less than $500,000 or so—less due diligence, for example, and no demand that all partners approve deals.

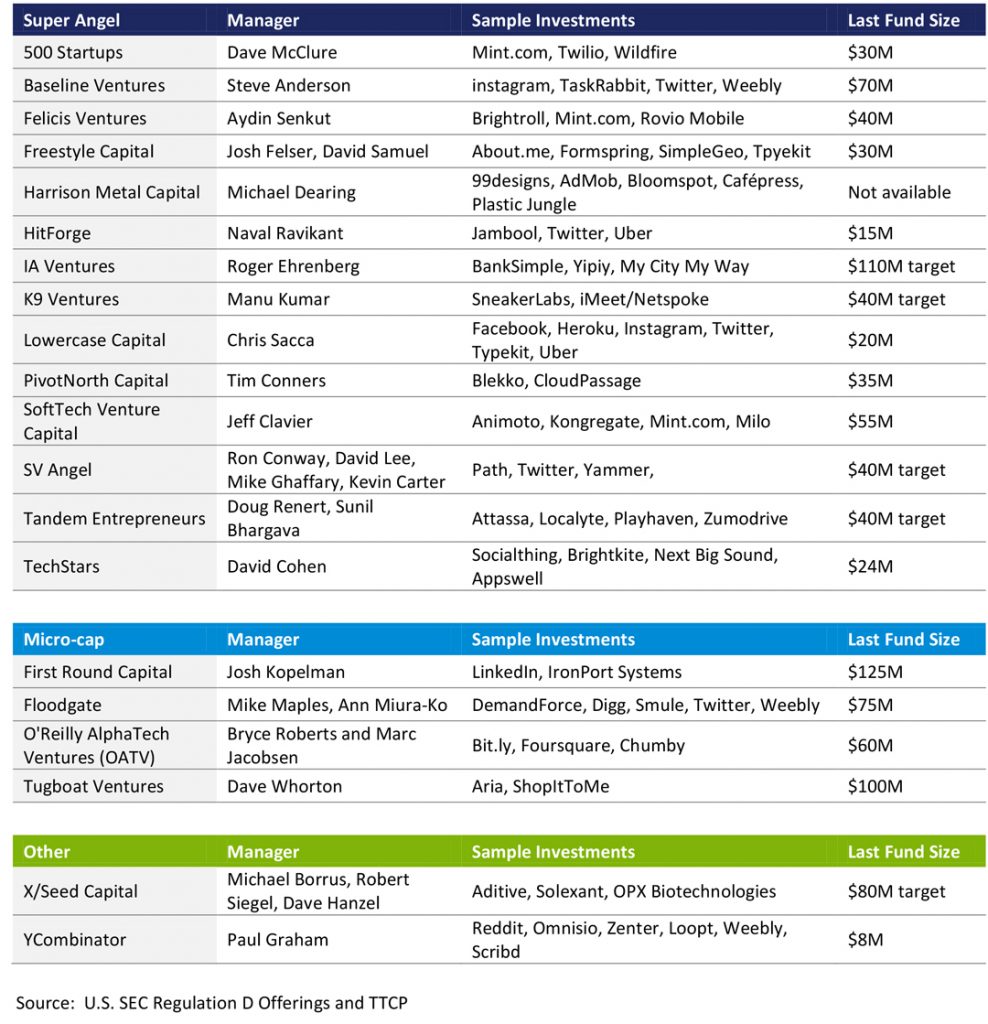

Still other VCs are outsourcing their seed programs. The Wall Street Journal reported in 2010 that firms including Norwest Venture Partners and Sutter Hill Ventures have invested in outside, super-angel funds. Norwest backed SoftTech VC, a fund run by angel Jeff Clavier, while Sutter Hill backed Naval Ravikant, a former venture investor and serial entrepreneur who started a seed fund called Hit Forge. Sequoia Capital has long had a relationship with the Y Combinator fund, giving the storied VC firm an early look at many embryonic start-ups passing through that seed program.

VCs view their seed programs differently. Some look at these micro-deals as low-risk options, a way to make sure they can participate in a company’s next funding round if it succeeds and grows. Other VCs consider seed financings mini Series A investments and may conduct more due diligence before investing. As one would imagine, venture investors taking the former approach are more active at the seed level.

The Rationale for Going Small – on the Wings of Angels

Why the rush to go small? Simply put, many traditional VCs feel they must have some presence in the seed market today to stay competitive. With many start-ups requiring less investment to scale up and get products out the door, non-traditional investors, such as angels and super angels, can fulfill these companies’ financing needs, at least for a few years. This new market dynamic has left VCs scrambling to get into some promising deals, and prompted some to re-think their business models.

The seed revolution started taking hold in the middle of the last decade amid profound technology shifts in the industry. At that time, many start-ups found they were able to launch products, earn revenue and even turn profits with very little outside investment, or none at all. These start-ups—many of them offering internet applications—leveraged cheap, open-source software and programming tools, as well as dramatically lower costs for computer memory, storage, and internet bandwidth utilizing the “cloud” to build their businesses. Some also outsourced core-programming tasks to developers in lower-cost markets like India or Eastern Europe. It was a far cry from the late 1990s, when most start-ups were forced to spend tens of millions of dollars on pricey technology from vendors like Oracle and Sun.

Shasta Ventures’ Jason Pressman was quoted in The Wall Street Journal even back in 2005 saying he’d been to a web-business conference at which some entrepreneurs described venture capital investment as “almost superfluous” because they could bootstrap their companies for so long. Indeed, companies including photo- sharing site Flickr, blogging site Weblogs, and wireless firm Android, whose technology now forms the basis of Google’s high-profile Android phone operating system, never raised money from VCs.

Most start-ups, however, ultimately saw value in raising some money from more experienced investors, particularly if they wanted a significant exit. Many also realized that traditional VCs could be valuable board members and supply helpful advice about strategy and operations, as opposed to the hands-free approach favored by many angels. (Angels and super angels often don’t take board seats.) Still, these companies found they didn’t need very much cash, while the business models of most VC firms were predicated on making larger, early stage investments of between $3 million and $7 million—too much for many of the new start-ups.

Enter the super angels. These hybrid investors—a cross between traditional VCs and angel investors, who traditionally write small, personal checks to friends or family members—rose up to fill the market gap. New super angels like Mike Maples, Aydin Senkut, Dave McClure, Clavier, and Ravikant actually raised small funds from outside investors, instead of putting only their own money to work. The funds were usually well under $100 million in size. But these managers generally still wrote small checks and did minimal due diligence before making investments. These investors followed in the footsteps of pioneering and still active super angel Ron Conway, who famously invested in tech stars such as Google as an angel in the 1990s.

Since then, other super angels have slowly graduated into the ranks of traditional VCs. Below is a table showing several of these super angel funds, including those that have “graduated” into what we call the micro-cap VC space as well as others with unique business models to provide start-up funding.

Harvesting the Crop

Managing seed investment programs is tricky for venture capitalists accustomed to investing in slightly more mature companies. Challenges can arise at various times throughout the investment process, particularly with successful investments that wind up requiring follow-on capital. Sometimes a VC firm will invest in a seed round as an option to invest in a later Series A—but the firm may not be invited to join the A round when it is finally raised. In that case, the firm is taking early risk, but doesn’t get a chance to participate in any potential company upside.

The business model and mindset for managing seed deals is also fundamentally different from a traditional, early stage program, and requires a new way of thinking for VCs. A seed company raising a total of $1 million in capital from a couple of seed investors, for instance, could generate great returns if it is sold for $50 million. Most $50 million exits for early stage companies, however, wouldn’t be considered successful, since investors likely put much more capital into those companies and would realize much lower returns.

We are following these issues closely because our own seed stage exposure is relatively high. In our 2007 vintage year fund of funds, which includes 2007-2010 vintage year funds, 20% of the investments were made at the seed stage. That is up from 12% in our 2002 vintage year fund of funds. Moreover, we are seeing this number increase again in our current fund of funds program, which has vintage years from 2010-2012.

Here are five specific examples of how our VC partners are managing seed programs, from investment through exit. The approaches are, we feel, representative of the various models VCs are using to do seed deals across the industry.

Manager 1: This firm has reserved 2% of its current $300 million fund, or about $6 million, for seed stage investments. The firm defines seed investments as deals of $300,000 or under. The deals are done quickly; the manager does not set the terms on the seed deals and does not take a board seat. But the deals have been numerous: about half the fund’s investments to date have been part of the seed program. Interestingly, however, if the firm decides to make a follow-on investment in a seed company, that money comes out of the firm’s subsequent fund, and not the one from which it made the original seed investment.

Manager 2: This firm is devoting a much larger, 25% of its current $400 million fund, to seed deals. It has a dedicated team to work on these small investments. The firm will use money from the current fund to do follow-on investments in seed companies. But if funds run low, it has the option to do crossover investments in the next fund.

Manager 3: This firm has more of a hybrid approach to doing follow-on investments in seed companies: If the firm decides to do a subsequent, Series A investment, the earlier fund that did the seed round gets its “fair share” and the later fund will then invest alongside the earlier one in a cross-over investment. If the seed investment was a note, the two funds split the investment 50/50.

Manager 4: About 15% of the investments made from this traditional, early stage investor are seed investments. However, these investments are not thought of as options to invest in the next round, which is more typical among other managers, but rather as a small, initial investment. For this manager, therefore, the majority of the seed investments have converted to Series A investments.

Manager 5: About 2% of the capital, or $15 million, of this manager’s 2007 vintage-year fund has been invested in about 30 seed projects. Seven of these have already become real companies and two are turning into significant fund drivers. Overall, it is expected that about 30% of these will convert to Series A investments. Most importantly, the manager’s early return forecasts from this seed program are to generate a 3-5x, and so the firm expects a similar amount of seed activity in its 2011 vintage-year fund.

Conclusion

Traditional VC firms are still experimenting with seed investment programs, and the industry will probably continue to offer up multiple models for running them. The jury is still out on how successful these programs will be for investors. While it is clear that former angel turned VC Peter Thiel’s $500,000 investment in Facebook—a company now thought to be worth as much as $100 billion—will go down as a huge winner, for instance, many other seed investments by VCs have yet to pay off big and many will be written off completely. It is simply harder to make educated investment bets on very small companies that may offer nothing but a talented, two-person team and an idea, as opposed to larger companies that may have developed actual products or even made some sales by the time they want to raise money. Most traditional VCs, however, expect most of their seed investments to fail and need only one or two winners for programs to be successful given the modest financial and time resources they devote to seed companies.

There also will likely continue to be stiff competition between super angels and VCs for seed deals. Super angels will argue that their quick decision-making and vast, current networks of other hot companies will serve seed CEOs best, while traditional VCs will counter that they’re better positioned to offer advice on company building and invest in later funding rounds to help small companies scale. Either way, it is clear that angels and super angels have not squeezed VCs out of the investing scene, as was feared two or three years ago. Both types of investors are actively jockeying for position in a robust environment for small, high-tech deals, and both stand to benefit from the seed investing trend.